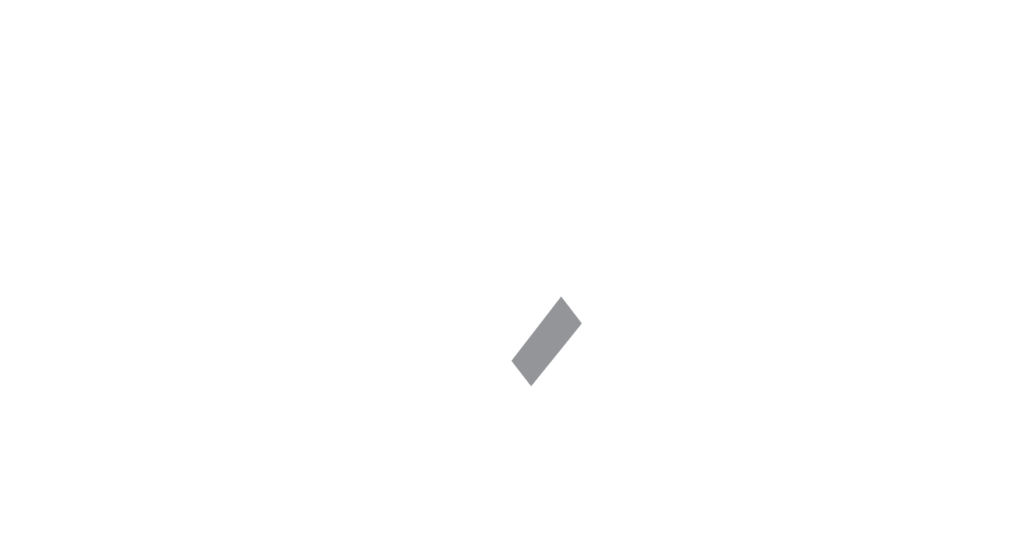

Elesin Oba is the latest release from Nollywood in a year that seemingly had a back to basics call for filmmakers, as a few movies leveraging on the mythical Yoruba history have previously debuted (King Of Thieves in April, Anikulapo in September).

In addition to that, it is an adaptation of a play by Wole Soyinka, Nobel Laureate, master playwright and writing genius, (yes, we are weighing in on the resulting twitter argument over Soyinka’s legacy and that is our verdict, we are shocked to even have to) so there are a lot of comparisons and expectations hanging over it at the time of release.

Throw in the controversy surrounding the Nigerian Oscar Selection Committee’s decision to rule all three movies unfit for submission to the Academy awards for Best International Feature Film, and the release of Elesin Oba on Netflix is to critical as well as entertainment expectations. This review will attempt an appraisal of both.

Elesin Oba is set in 1943, in the middle of the second World War. It tells a true story Soyinka says happened three years later, and paints a small, poignant scenario of the white man’s assumed superiority over ancient traditions, and how colonial masters think they carry with them the only correct version of what is right and wrong. The titular Elesin Oba (Odunlade Adekola), the king’s horseman is loyal to his liege in life and death, and as is tradition, he will wilfully commit ritual suicide a month after his king’s passing to accompany his soul to the afterlife. His chosen resting place is the market, where he has long enjoyed the comfort and company of the Iyaloja (Shaffy Bello), the mother of the market, and her daughters, and desires at his passing to rest in their bosoms one final time.

In preparing for his final rites he is distracted by a beautiful woman, and he desires to get married, make love to her, and leave with her his seed before his death. The Elesin’s sexual profligacy is well known by the Iyaloja, even more in the play, and being the night it is, she will not refuse him this request. She leaves him, however, with a warning to not get carried away by earthly pleasure on this night of heavenly aspiration, a statement that will prove almost prescient.

It is important she reminds him of this, for a failure to fulfil his duty will mean the king’s soul will roam the earth untethered, unwelcome, and unconnected to his forefathers. The consequences of this are not stated implicitly, but they can be assumed to be of the highest severity, for it is something that no character even envisages. Importantly, the Elesin does not even need factor in these consequences in his action, he takes this suicide as not just a duty but an honour, the highest of those he has had from his birth and in fact, the climax of his entire existence.

It was important to thoroughly contextualise this act of ritual suicide in the mind of the individual committing it and the town in which it occurs, analysing it at surface level will leave you with a understanding of it akin to Mr. Pilkings’, the white district officer who moves to stop Elesin’s act of sacrifice and, putatively, save his life. He is successful, depending on your definition of the word in this context, and the Elesin is robbed of his glory.

It is at this point, after Elesin is stopped from completing his rites, that the watcher is called upon for their own input, for as the facts of the story have been given, a verdict is expected, answers to two questions.

First, of the legitimacy of the Colonial officer in preventing a “native” practice that was going to harm no-one in happening simply because it contravened his own laws, laws whose jurisdiction should not extend an inch outside the confines of his own country, and certainly not across the Atlantic to another continent. Second, and the one more difficult to ascertain, is Elesin’s failure simply as a result of the white man’s interference, or was he too weak to depart in the moment he spent his entire life preparing for? Iyaloja certainly thinks the latter, going by her scathing condemnation for Elesin after his failure.

To answer these questions, you may need the extra layer of context the play provides, but that is said with no disrespect to Biyi Bandele’s adaptation. The movie is a near perfect mirror of the play’s events, with no major changes happening to the story line or characterisation in its transition to the big screen. Some of the dialogue is lost in making this journey, though, presumably for want of time, so that two of the most important scenes of the movie, which sheds the most light into the two primary questions as listed above – Olunde’s (Elesin’s son) conversation with Jane (Mrs. Pilkings), and the discussion between Iyaloja and Elesin after his failure – are clipped, with the lost words of dialogue standing in the way of providing the watcher a full understanding, and enjoyment, of these critical scenes.

The problem with The King’s Horseman, rather, the problem with the audience of the movie is that many will want and expect some heartstopping action or pulsating moments of suspense, and get disappointment in its place, for the real action happens in the subtitles where the conversation is being translated. It is important to bear in mind that, being adapted from a play, and by Wole Soyinka no less, Elesin Oba has as its biggest weapon its writing, so nothing should be expected to top this.

To put this writing into film requires masterful acting, proper direction and as Soyinka himself is quoted to say in the preface to the play and movie, “music from the abyss of transition”. Each of these lives up to the billing, and Odunlade Adekola is able to shine in another important role in this genre, after his performance as king in Femi Adebayo’s King Of Thieves from earlier this year.

Another member of the cast, singer Olawale “Brymo” Oloforo, excels in two of these elements, and Shaffy Bello puts in a staunch performance as Iyaloja. The setting of the movie in early 1940’s Nigeria’s is also well done, and there is never any prop or scene that makes you doubt this is actually late colonial Nigeria.

Elesin Oba is the work of two masters, Soyinka’s brilliant writing brought to authentic life by Biyi Bandele’s mastery of direction and screenplay. There are no real heart pounding dramatic moments, but if you came expecting them you are probably in the wrong theatre. What you do get is a perfectly executed depiction of Yoruba culture viewed as a microcosm of a single monumental night, and it will leave you to reflect on the mythology of transition, the legitimacy of ancient, sacred ways and how a disrespectful, self-appointed overlord tramples on them without understanding or jurisdiction.