“I think everything in life is Art”.

The quote by popular English actress Helena Bonham Carter carries new meaning with each consideration, from the innocuous smile to every perfect ray of sunshine, her quote refers to the scenic moments in everyday that come impregnated with emotion.

Naturally, life and art share many of the same qualities, one of which is life’s dynamism — As life changes regularly and is always in perpetual motion, so also is art. Since the dawn of time, and beginning with simple markings on the walls of caves where the early men dwelt — art has come a long way, evolving into various kinds, types, and styles that exist in the present day. In the 21st century, art exists in multiple mediums for consumption — some of the most popular being books and movies. It is no coincidence that these mediums are necessarily connected and regularly borrow from each other; it’s the beauty of art in and of itself.

Adaptation (as such borrowing is called) is not a novel concept. To define simply, adaptation is the process of converting a work of art from one form or medium to another, most often to appeal to a different audience. A striking example is virtually all the works of William Shakespeare — adapted from written works to plays and performances and eventually eternalised as movies. A very recent example can be seen in the blockbuster franchise, “Harry Potter” by JK Rowling which started with the stroke of a pen and took off like a wild fire before also getting adapted for the big screen, and even as stage plays. Bringing it home, another example is the work of Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka. His play ‘Kongi’s Harvest’ was adapted for film in 1970, a landmark event in Nigeria at the time. Literature exists, in this case, as a wealthy source of cinematic content.

“With hundreds of good — nay — great works of literature to choose from, why has Nollywood remained blind to the writing on the wall?”

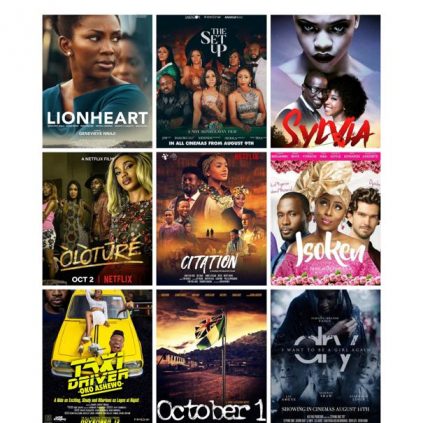

The efficacy of literary adaptation is obvious without question. Many movie successes that started off as books are standing proof. Characters burned in our memory from Lord of The Rings, James Bond, The Godfather, IT, Hannibal, Game of Thrones, and hundreds more were once merely markings on pieces of paper. These examples easily come to mind without having to look far and wide. However, why then have Nigerian movie makers not taken the hint despite the wealth of Nigerian literature? With hundreds of good — nay — great works of literature to choose from, why has Nollywood remained blind to the writing on the wall? Between 1970 and now, sadly only a handful of adaptations exist, so few that they’re like diamonds in the rough. Thankfully, Achebe’s novels; ‘Things Fall Apart’ and ‘No Longer At Ease’ were combined and adapted into film by Francis Oladele, renamed ‘Bullfrog in the Sun’.

This failure to capitalise on the abundant wealth of stories and characters available in Nigerian literature cannot be blamed on a lack of relationships between the robust Nigerian literary scene and it’s filmmaking counterpart. The relationship exists, but it has been starved over the years and exists in virtual nonexistence. As such, it is important to investigate and find out why this crime of ignoring creative gems continues unabated.

The challenges faced by Francis Oladele in his adaptation of Achebe’s books stands as one reason film makers may be shying away from the subject; Government interference. Oladele would ordinarily have retained the title of Chinua Achebe’s book, “Things Fall Apart”, but the government of the time, still licking its fresh wounds from the civil war censored Oladele’s work heavily, thus leaving him with little choice but to adopt the unrelated title “Bullfrog in The Sun”. In a craft as meticulous and delicate as filmmaking, even the title must be almost perfect, considering the source material. A substantial amount of great Nigerian literature, especially those that directly reference the government or refer to history will likely rile up whatever government is in office, and no filmmaker wants their work challenged by government or censored from screen.

Another possible reason could be the effort required to acquire intellectual property (IP) rights. Adaptation involves the conversion of original works into other forms, and the legalities that come with such use of intellectual property. Without proper permissions, a filmmaker, regardless of his intentions, would be committing intellectual theft if he does not get approval from the author of the original text before embarking on an adaptation. As such, the decision to adapt literature must be followed by a push or attempt at contacting the author, and often, an offer of royalties for such use of IP. Nigerian filmmakers may not want to go so far, especially considering that intellectual property rights is a concept that is only recently coming to the forefront of legal discourse in Nigeria.

Filmmaking is a financially intensive endeavor, this much is true. Combined with that fact that an author has the right to dictate how his works should be converted and used, it may seem much easier to start from scratch and create original content, free of the heavy baggage of author oversight and influence possibly stifling a film makers creativity.

“Adapting a work of literature pulls characters straight from frozen ink and dusty books and breathes life into them — life filled with human emotion, facial expressions, and character.”

Although the challenges of literary adaptation looms large in the horizon of filmmakers, it is good to remember that nothing good comes easy, it is up to the toughest on the scene to step up to the plate and get the work done. When done right, the pros outweigh the cons in this scenario. Adapting a work of literature pulls characters straight from frozen ink and dusty books and breathes life into them — life filled with human emotion, facial expressions, and character. The act alone of converting book to film immortalises the work of art, as well as presents it to a much larger and much more voracious audience. What’s more? A filmmaker given free rein on works of literature can creatively present these works in a different context, shining a more relatable light on the chosen literature, whereas before adaptation to film, an acquired taste may be required to enjoy them. All this happens while jobs are created for the filmmaking crew and cast.

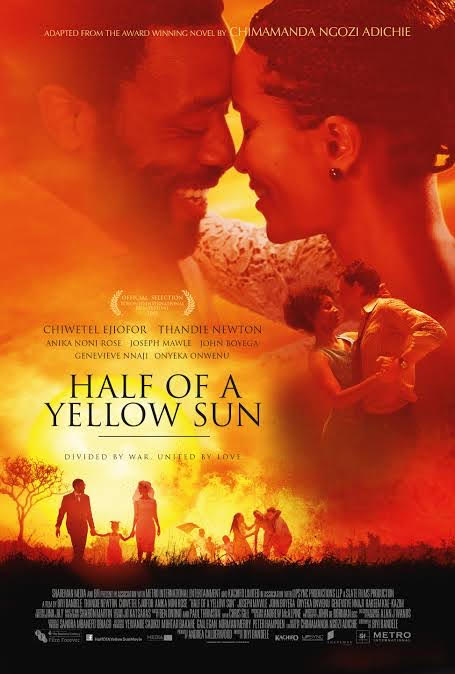

Adaptation is a creative challenge to film makers. It’s an opportunity to annex their own creative vision with those of the original writer, while staying true to a central storyline. The adaptation of Chimamanda Adichie’s ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ is a testament of all the benefits of converting book to film.

The recent partnership between Mo Abudu of EbonyLife and Netflix for the production of films and series licensed to the service may indicate that the Nigerian film industry is finally looking to its literary counterparts for creative content. A highlight of this is the adaptation to film of works from two critically-acclaimed Nigerian authors; Lola Shoneyin’s debut novel, “The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives”, and Wole Soyinka’s “Death and the Kings Horseman”. One of these two works is planned to be released on Netflix sometime this year.

📣We’ve got MAJOR news for you today! Netflix has partnered with acclaimed producer @MoAbudu to bring you two of Nigeria’s most beloved literary classics to screens around the world! 📚🎥 pic.twitter.com/3zAE4zAndH

— Netflix Naija (@NetflixNaija) June 12, 2020

I’m teetering off the edge of my seat in anticipation of these films as I’m certain Mo Abudu has the best interests of the Nigerian literature community at heart. It will definitely be a joy to watch where this first steps lead the Nigerian literature and movie communities.

![image0[1093] image0[1093]](https://txtmag.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/image01093-pigu8a4b8zyc6kgebsd63mwsjmaak6pcc1b9ibawxy.jpeg)